November 21, 2007

MQ-9 UAV Sees Combat

Hoover Dam illustration by Hugh Ferris

The MQ-9 Reaper, the first UAV designed for combat to be put into service, has seen its first action:

The Reaper, the Air Force's unmanned aerial attack vehicle, was operating over the Sangin region of Afghanistan on the hunt for enemy activity when the crew received a request for assistance from a joint terminal attack controller on the ground. Friendly forces were taking fire from enemy combatants. The JTAC provided targeting data to the pilot and sensor operator, who fly the aircraft remotely from Creech Air Force Base, Nev. The pilot released two GBU-12 500-pound laser-guided bombs, destroying the target and eliminating the enemy fighters.

(Some of the details in the article above, from the “official web site of the United States Air Force”, differ from those in the story as reported by the Air Force Times. And The Register has its own take.)

Depending on which particular UAV was involved in this story from last week, the Reaper's first use in combat might have been particularly tragic:

Extraordinarily keen observation by a British Royal Navy officer narrowly averted a potentially tragic friendly fire engagement using a Predator or Reaper UAV.

The UAV operator had been given clearance to engage the targets – a group of 7-10 men - in an operational theater. The men had been identified as hostile forces.

The navy officer, believed to be working as part of a joint US-UK UAV force operating from Creech AFB, Nevada, noticed that the men, while dressed in local attire, did not actually walk in the same manner.

This single observation led to the potential engagement being called off. The group were in fact special forces.

November 17, 2007

Why Did Symbolics Fail?

Paul McDonough, Woman Sunbathing, Portland, Oregon, 1973. See also New York City 1968-1972.

Dan Weinreb, Symbolics co-founder and significant contributor to the design of Common Lisp, has an awesome new blog which has another great new post, “Why Did Symbolics Fail?”

The world changed out from under us very quickly. The new “workstation” category of computer appeared: the Suns and Apollos and so on. New technology for implementing Lisp was invented that allowed good Lisp implementations to run on conventional hardware; not quite as good as ours, but good enough for most purposes. So the real value-added of our special Lisp architecture was suddenly diminished. A large body of useful Unix software came to exist and was portable amongst the Unix workstations: no longer did each vendor have to develop a whole software suite. And the workstation vendors got to piggyback on the ever-faster, ever-cheaper CPU’s being made by Intel and Motorola and IBM, with whom it was hard for Symbolics to keep up. We at Symbolics were slow to acknowledge this. We believed our own “dogma” even as it became less true. It was embedded in our corporate culture. If you disputed it, your co-workers felt that you “just didn’t get it” and weren’t a member of the clan, so to speak. This stifled objective analysis. (This is a very easy problem to fall into — don’t let it happen to you!)

He also comments a bit on Eve Phillips' 1999 article, “If It Works, It’s Not AI: A Commercial Look at Artificial Intelligence Startups”.

Paul Graham's comment from the news.yc thread:

DLW's thesis that Symbolics lost as part of the general losing of custom hardware (including all the parallel computer companies) is basically correct. Lucid on Suns was as fast as ZetaLisp on Symbolicses.

But not so fast that that alone made me switch. What made me switch was that Lisp machines (both Symbolics and LMI) were so gratuitously, baroquely complex. The manuals filled a whole shelf. Each component of the software was written as if it had to have every possible feature. The hackers who wrote it all were the smartest and most energetic around. But there was no Steve Jobs to tell them "No, this is too complex." So the guy in charge of writing the pretty-printer, for example, would decide. "This is going to be the most powerful pretty-printer ever written. It's going to be able to do everything!"

...

Unfortunately this complexity persists in Common Lisp, which was pretty much copied directly from ZetaLisp. In fact, both of the worst flaws in CL are due to its origins on Lisp machines: both its complexity and the way it's cut off from the OS

And then there's the reddit thread on pg's comment.

November 15, 2007

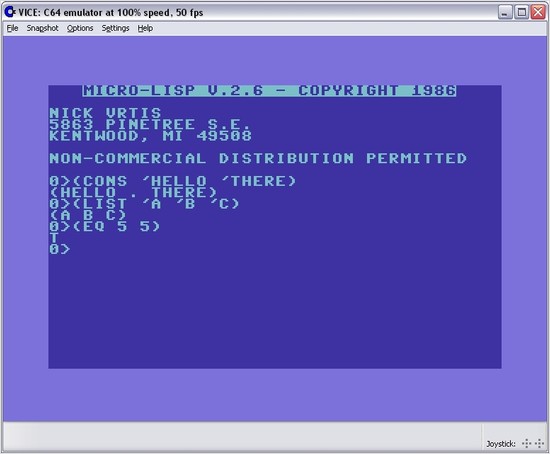

Micro-Lisp

From NovaCode:

After my last post I wanted to check to see if there was a Lisp interpreter available for the Commodore 64. I found one! It is called Micro-Lisp.

Looks like Micro-Lisp appeared in volume 8, issue 6 of Transactor, in 1988:

November 07, 2007

CMU Wins 2007 DARPA Urban Challenge

11 robot vehicles entered the course and 6 were able to finish. CMU came out on top while Stanford got second place—a reversal from 2005's Grand Challenge. Wikipedia has the complete race results.

I took pictures, and some video. So did everyone else. There's a torrent for the complete DARPA webcast, but the video was very glitchy for me.

Highlights:

- The customer reviews of Victorville's hotels (e.g. “On this stay I was alarmed by the condition of my room and was concerned about the types of people that were loitering about the walkways. It seems this hotel is housing alot of displaced people, who seem to live there on a permanet basis: also alot of male truck drivers who watched us when we used the spa. This is not a hotel you would take your family to.”).

- Hardly any militaristic cheerleading from the race announcers.

- Terra Max trying to plow through a building.

- MIT's vehicle smashing into the Cornell bot.

- The moment when several bots reached a 4-way stop at the same time, and everyone watching the video feed realizing that this could be the end of the race if the bots deadlocked, and then seeing the bots eventually work it out for themselves.

- Commentary from MythBusters Jamie Hyneman and Grant Imahara, and overall a much better effort by DARPA to provide info during the race compared to previous years.

- Being able to stand within a few feet of much of the course and practically feel the vehicles driving by.

- DARPA's decision to give teams the list of GPS waypoints only 5 minutes before the race, compared to two hours in 2005. Some people felt that in 2005 CMU violated the spirit of the competition by having a dozen people process the waypoints into a final route for their vehicle.

- This comment from a DARPA traffic vehicle driver: “...this was not a game of horseshoes, having participated today for more then seven hours with the bots as a traffic vehicle driver you get a real taste of the what ifs when you are face to face with a vehicle like Terramax, I had to take evasive action to keep from getting run over today.”

Not as highlighty:

- The Circle K I stopped in that had 2 working gas pumps out of 36, and a bathroom that made me think of a Francis Bacon painting.

- DARPA's scoring process being pretty opaque—what scores did the teams get? And why? DARPA hasn't even revealed which vehicles got 5th and 6th place, as far as I know.

Overall the teams did better than I expected at handling the urban environment, with its lanes and curbs and moving obstacles.

November 02, 2007

11 Finalists Chosen for Urban Challenge

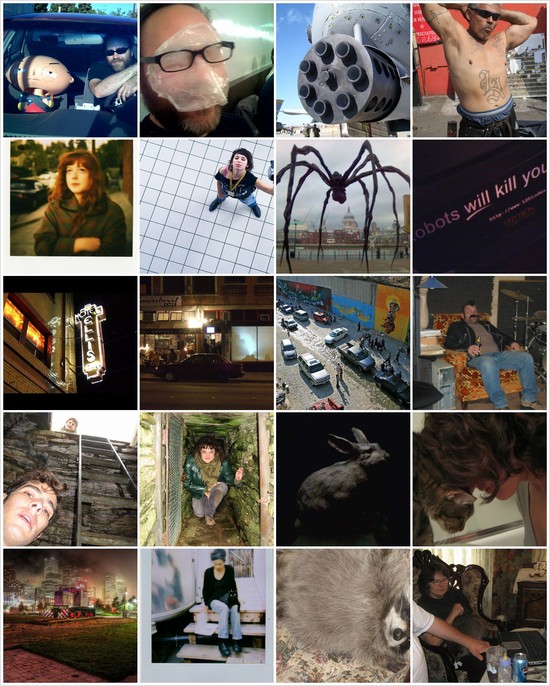

My recent flickr favorites: 1. another wednesday in silverlake, 2. Untitled, 3. The business end of an A-10, 4. style, 5. autumn in l.a., 6. BRT_1543.jpg, 7. Spider faces down St. Paul's, 8. no they wont, 9. Ellia Hotel 802 E. 6th St. 90013 -- Skid Row, 10. DSCF5009.JPG, 11. As the River Runs Softly on By..., 12. Billy-Bob-Bo-Bob-Busse, 13. To get in you have to climb down, 14. Crawling out of Unstan, 15. hare, 16. head butt, 17. Night Train, 18. sarah and dover, 19. Bandit snuggles, 20. A normal day with my mom and her friends

THe DARPA Urban Challenge was supposed to have 20 teams competing, but after the qualifying runs this week DARPA has judged that only 11 autonomous vehicles are safe enough to become finalists [via Danger Room, which has had excellent coverage of the Urban Challenge so far].

DARPA's top dog warns the media that the robotic vehicles in tomorrow's Urban Challenge race will be unpredictable and will quickly get “random”. “We really don’t know what they’re going to do,” said Dr. Tony Tether, but he assures everyone that safety will be the number one priority for both spectators and the crazy stunt car drivers who will get in the way of the robots.

As the qualification rounds came to a close, Dr. Tether personally inspected the runs to make a better determination of who would make it into the race. He recalls one scary incident where Team Lux's robot did a sudden U turn and accelerated towards the van that Dr. Tether was riding in. “That vehicle was coming straight at us… we were screaming pause pause!,” referring to the remote kill switch that officials carry during the race. Someone eventually hit the switch and killed the bot only a few feet away. “That reminded me, this was not a game,” Dr. Tether said.

Many teams are understandably upset at DARPA's decision to only pick 11 teams for the finals, but Dr. Tether assures that his trained staff had all the data necessary to make the tough choices. The initial cuts were for safety reasons because DARPA didn’t want bots to collide with other bots. Slower vehicles that would have caused traffic jams were the last ones to be eliminated.

Saturday's race could conceivably have all 11 robots on the course at the same time. Dr. Tether told us there will be staggered starts and the bots won't go to the same spot at the beginning.

I'll be in Victorville tomorrow, watching out for rogue carbots and marginal people.